I spent the morning in synagogue, at Shir Tikvah in Minneapolis, with a new friend and coworker of Gabi's. The service was very good, although before I move into reflections on the theology and meaning of the service, let me make the most secular of admissions: I love going to High Holiday services because it means I am sitting in the midst of not just hundreds of fellow Jews, but also dozens and dozens of women who have the same curly, willful, frizzy, uncontrollable hair. I love it. In a world where I'm usually around the straight-haired (even if not always immaculately coifed) I love being around a bunch of women who, like me, spent their childhoods hating their curly locks because no amount of blow-drying, curlers, or chemical straighteners would ever enable them to pull off a Farah Faucett 'do. It's brilliant.

But, I would remiss if I let you think that I spent three hours this morning contemplating hair. No, I spent that time (and several hours over the last few days, reading and studying so that I would be "ready" for my precious time in synagogue) thinking about the three things that, during the High Holidays, we are reminded that we must always do: tefilah, tzedekah, teshuva.

I always wince before translating these words, because they are mistranslated so often. Still, bear with me as I fumble through...

Tefilah, the easiest to translate, basically means "prayer." In this context, it means to study Torah, pray, and lead a spiritual, prayerful life.

Tzedikah is most commonly translated in English as "charity," partly because of the "Tzedekah boxes" that are kept in many Jewish homes so that families can gather money that will be given to the needy or otherwise used to do good. However, tzedekah is more accurately translated as "righteousness," or the using of money or other tangible effects to help those who are oppressed, assist those in need, and fight social injustice. In the Talmudic tradition, the money that goes into that little box is not so much "pennies for the poor" as it is "pennies to end poverty." The difference is significant because it means that we are called not just to give, but to give a damn.

Finally, teshuvah is commonly translated as "repentance." In this sense, the Days of Awe are all about trembling before G-d, fearing G-d's judgement, and confessing our sins. This insistence on sin and judgement was always a barrier for me in my desire to reach any kind of deeper spiritual understanding of either myself or my heritage. Then, last year as I was studying during the High Holidays, I learned that the more literal translation of teshuvah is "return," as in returning to your intention to lead a moral, hopeful, positive life; returning to Torah if you haven't read your parashahs every week as you had intended; returning to the goal of being the person you want yourself to be. Returning to the person G-d intended you to be.

I was so moved and joyful to learn of this more literal translation, because it is much more positive and affirming, and makes so much more sense in terms of other things I've learned over the last several years about Torah and Jewish ethics and spirituality. Repentance doesn't work so well for me, and I suppose, a lot of other people too. Repentance feels too often like spiritual self-flaggelation. To be completely mundane: I've been trying really hard to lose weight. Counting calories and all that. Some days I'm just out of control, however, and I binge. These days, it's not even so much that I eat things that I don't want to be eating. I might have wanted the first bite, but not the tenth. It gets to a point where I'm eating on auto-pilot or, even worse, in some form of punishment: I'm such a pig that I might as well eat these cookies (crackers, whatever) and be fat and ugly and unhealthy.

When I'm in a state like that, repentance is the worst thing for getting me back in balance. If guilt worked, if bashing myself with all the should-haves worked, I never would have gotten fat in the first place. When I'm in that state, repentance just adds to my sense of failure and that overwhelming feeling that I'm not even worthy of being healthy and happy.

Return, on the other hand, can lift me out of my hole. It's positive and affirming. Look, I can say to myself, I've already been able to follow my goals well enough to lose almost 50 pounds since my highest weight. That's right. Fifty pounds. I can do this. I have been doing this. Return is possible, because it's taking me back to a place where I've already been before. I've been balanced and positive and I've done really well. Return is accomplishing, again and a little better, what I've already done in the past.

Repentance, at least for me, is more about looking at some "place" or state that I've thought I ought to be able to attain, because of course I think I should be able to meet the overwrought, underweight, uber-successful standards I see on t.v. and magazine, and then castigating myself for not attaining that model of perfection.

I don't mean to suggest that all moral and ethical decisions are on the same level as the decision of whether to eat a small piece of chocolate or the whole bar plus several crackers with peanut butter plus whatever else is even moderately edible.

Rather, my point is that we all falter and fumble, and whether it's about eating or how we treat our beloveds, whether we help strangers or pocket the twenty dollar bill we find in the public restroom, ethical questions big and small have the same kinds of aspects. We have an image in our head of who we want to be and a sane, soft-spoken voice that tells us when we are about to stray. We make decisions, big and small, that impact our ability to uphold our image of ourselves. And the more stress and chaos that fills our minds, the more difficult it is to hear that soft voice that knows what we're really about. And finally, no matter what we choose to do ~ and how many excuses we could muster about our bad decisions ~ we are the only ones ultimately responsible and accountable for our actions.

And what is so profoundly beautiful to me in the Jewish tradition is that our spiritual year is set up not just to remind us of the importance of tefilah, tzedekah and teshuvah, but also to allow us a fair amount of time so that we can contemplate deeply and begin the process of being accountable. We aren't expected to acknowledge our failings, apologize, make amends, and make a plan to move forward in just one day or two. The entire month of Elul, leading up to Rosh Hashanah, is spent preparing (for example to do as I did and evaluate my relationships and choices during the previous year as well as study Torah commentaries before going to synagogue so that I could be more fully present when I got there). Rosh Hashanah brings in the Days of Awe, ten days to reflect, make amends, and prepare ourselves to do that which we are called to do: have a moral, spiritually positive life, to work to end oppression, injustice and poverty, and to return, regardless of our faults and failings, to that vision of ourselves and our communities that are worth working for.

Rabbi Steifel said today, "The greatest heresy in Judaism is to believe that the world must be as the world is." We are called to be change agents, for ourselves, our communities, our world. The ethic of co-creation is key: our role on this earth is to work in partnership with G-d, to unleash the godsparks in each other and all living things and bring about the constant renewal and re-creation of the world.

I'll close with one of the meditations from the Rosh Hashanah service (from Gates of Repentance: the New Union Prayerbook for the Days of Awe, 1978):

Be among those who cherish truth above ease and whose prayers are shafts of light in the darkness that, otherwise, would envelop us. Be the same within and without. Aspire to be loving, compassionate, humane and hopeful. Become the prayer for goodness your lips have uttered.

*****

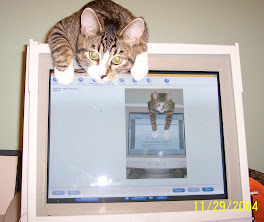

Photo credits: the pic up top is from the website MyJewishLearning.com, one of my favorite sites. They have just about everything you could hope to find on a site devoted to learning about Torah and Judaism, and they bring in commentary from many perspectives, traditional, conservative, reform and progressive.

No comments:

Post a Comment